Speech Transcripts

CSO Rosenthal Archives)

Music in Modern Life

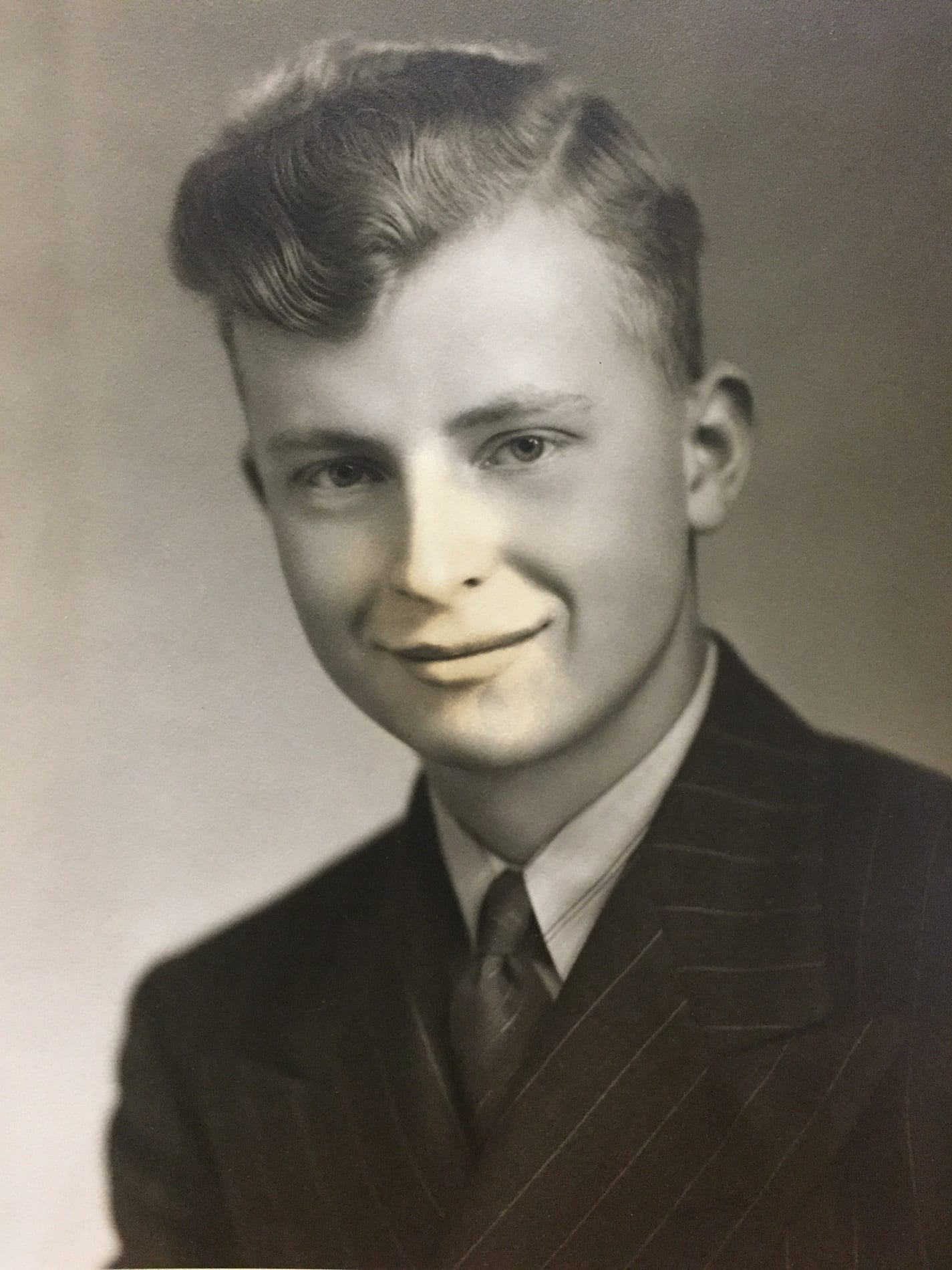

1939 Valeditory speech given By Adolph Herseth

at his graduation from

Bertha High School

When man left the most primitive type of existence and began to better his station on earth, he also developed one thing which has ever since been one of the most important elements in life – music. Music has been associated with the development of civilizations, and has had a big part in building the civilization within which we live today. Men have used music or rhythms of certain types to distinguish themselves from one another, and none of the arts can claim precedence over music. It is with these facts in mind that I wish to present you with my ideas on the place of music in life today.

Music, along with literature and the rest of the arts, enjoyed a revival and sudden growth after the Renaissance. Previous to this, all such had been rather subdued for centuries. But even before the Dark Ages, when the ancient civilizations flourished, music had already gained a good foothold. Man in those days often wrote history in verse form, and then sang it. Traveling bards and players who went from town to town singing and playing were numerous and popular. Music, even then, was assuming a place of prominence, not only in the leisure life of men, but also in the professional side of life.